Night Bird Song

About

Track Listing

Opening (Pub rights to Chapin/Pavone/Sarin) 2:45

Alphaville 7:03

Night Bird Song (Pub rights: Thomas Chapin and Mario Pavone) 8:46

Cliff Island 8:22

The Roaring S 5:49

Aeolus 6:01

Tweeter's Little Adventures 6:51

Changes Two Tires 5:21

Recording Information

Thomas Chapin - alto sax, sopranino sax, flute, alto flute, alarm clock

Mario Pavone - bass

Michael Sarin - drums, percussion

All compositions by Thomas Chapin (Peace Park Publishing), except “Opening” by Chapin, Pavone & Sarin, and “Night Bird Song” by Chapin and Pavone (Peace Park Publishing & Pavo Publishing).

Thanks to Kampo Cultural Center, Gabrielle Riero, Alex Abrash, etc. The Trio—music and choices. Terri—support, Gil Barretto, Bill Singer—good repairs!, David Baker, Bob Ward, Knitting Factory.

Recorded live to DAT 8/29/92 and 9/29/92 at Kampo Cultural Center, New York City. Engineered by Dave Baker, assisted by J’ Kiel Digital. Editing by Bob Ward. Post-production master by Robert Musso (1/21/99). Design by Dave Bias.

“Cliff Island” in memory of Nancy Chapin (1918-1991)

“The Roaring S” and “Aeolus” dedicated to my brother Ted

NIGHT BIRD SONG is the property of Akasha, Inc.

Liner Notes

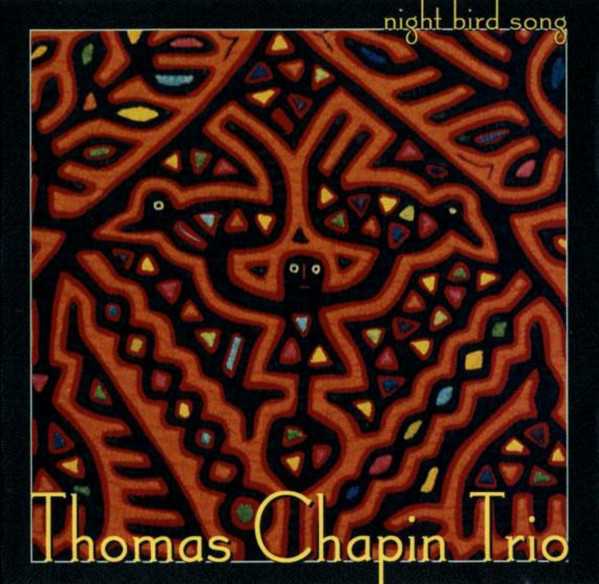

Preface note from Terri Castillo-Chapin: NIGHT BIRD SONG is the last CD album to be released that Thomas Chapin himself personally produced. It was Thomas’ decision that NIGHT BIRD SONG (released in 1999) would follow the release of SKY PIECE (1998). Only the post-production master, booklet design, liner notes and photos were not supervised by Thomas. The CD master was done in 1999 by trusted friend and gifted engineer Bob Musso. Thomas selected the cover art. It is a detail of a mola cloth collected during a cruise-ship stopover in the Blas Islands of Panama while he toured with Lionel Hampton in the 80s. It was a favorite in his collection, and so reflects the luminous spirit that was Thomas Chapin himself.

NIGHT BIRD SONG LINER NOTES by Larry Blumenfeld

When Thomas Chapin died at age 40 in February 1998, after a year-long bout with leukemia, the music world mourned the untimely loss of a man and his music. And it celebrated his promise, sensing something to hold on to, maybe even to build upon. A saxophonist of monstrous chops who was proficient on several horns, one of few true flute masters of his generation, and a significant bandleader and composer in his own right. Chapin nonetheless defied characterization by a single image or sound. He was a restless instigator of equal parts beauty and subversion. For these reasons, the arc of his career corresponded less to common categories of his day (“downtown,” “mainstream,” and the like) and more to the flight paths of bird he seemed to favor in song titles. With grace and individuality, Chapin took us places—lofty and striking and sometimes dangerous—that forced a change of perspective.

That’s why this recording, a 1992 session of Chapin’s trio with bassist Mario Pavone and drummer Michael Sarin, is both essential and satisfying. It takes us back in time to formative flights, enhancing our appreciation with telling details and brand-new angles. Chapin had placed the tapes of this session aside, hoping for the perfect moment for its release.

The trio would remain intact through the years that followed. Occasionally, Chapin would add horns or strings, but the group remained at Chapin’s creative core. “He felt we had happened onto something,” Pavone recalls of this recording, “that we had really captured something special about the point this trio had reached.” The bassist, who enjoyed some two decades of collaboration with Chapin, doesn’t elaborate: There was a deliberate mystery to Thomas Chapin’s achievements. Pavone knows that by now.

This session provides some obvious points of reference in terms of the trio: three compositions, “Alphaville,” “Night Bird Song,” and “Changes Two Tires” appear on Sky Piece, Chapin’s dazzling 1998 trio recording. And although the differences are subtle—there were no radical reworkings in the intervening years—on these 1992 tracks we sense a different energy, one that speaks of moments of creation. Also, Chapin was a master of context and segue: Here, the tracks are interwoven into a different fabric, one that also documents memorable (and previously unrecorded) compositions like “Aeolus” (God of the Wind), and “The Roaring S.”

“Eternal Eye” is a brief prelude that hints mightily at the soaring, searching beauty to follow. Chapin’s full-bodied flute carries the statement with only the sparest of accompaniment from Pavone and Sarin.

Its sweet rubato makes the tick-tock intro and ringing alarm of “Alphaville” come as a bit of a shock. That’s probably the way Chapin wanted it. An allusion to the science fiction film classic of the same name by French director Jean-Luc Godard. It’s also a reflection of Chapin’s state of mind regarding music: “The point is to stay AWAKE and alive to what is going on,” he wrote in liner notes to his 1996 release, Haywire. What’s going on here, musically, is a series of deftly crafted improvisations over various incarnations of a slightly menacing, mechanistic theme. First drums and saxophone play melody over clockwork bass, with Sarin keeping time; then Sarin interprets as Chapin and Pavone play the mechanical vamp. Each segment, each solo, works like a scene from a film. There’s an unsettling quality to it all, but not without some humor—a surrealist smirk with a larger point.

As presented here, the initial bass tones of “Night Bird Song” seem to pick up from Chapin’s final honk in “Alphaville.” But the song offers a very different state of mind: The sort of focused and refined reflection Chapin offered his collaborators and listeners on a regular basis. Although Pavone’s bass figure (upon which Chapin built this melody) sounds a bit like a Moroccan sintir line, the inspiration for this tune is much closer to Chapin’s New England origins. As quoted in the notes to Sky Piece, Chapin had referenced a stirring moment during a Connecticut stroll: “One night, in the wee hours, I was walking through a silent, sleeping neighborhood in the suburbs and heard a marvelous bird singing in a tree. It sang for about twenty minutes, never repeating its phrases, improvising away as I stood motionless, just out of the beam of the street light.” By the final section of the tune, Chapin can be heard swinging forcefully over a flamenco rhythm, dropping clues to the influence of one of his heroes, Rahsaan Roland Kirk—first through the muffled overtones of an aluminum can used to mute his alto horn, then through a chorus of sopranino and alto saxes played simultaneously.

The sopranino, a novelty horn in some players’ hands, is one that Chapin has distinguished himself on with as much individuality and authority as on alto sax or flute—in fact, it was a favorite mode of expression for him. Chapin’s voice on Eb sopranino carries “Cliff Island,” whose introduction echoes a bit of Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman,” but whose serpentine sopranino horn-and-bass figures are Chapin’s alone. Here again, images of New England and of the natural world were inspirations, this time of a favorite aunt in Maine; the piece’s ebb-and-flow calls to mind shards of sea glass, starfish, lobster pots and the like.

In Chapins’ brief handwritten notes, “The Roaring S” recalls the narrow S-shaped channel of rushing water that resulted when he and his brother, Ted, created a dam in a brook during his childhood. It’s also a testament to how, in general, Chapin could channel energy so that it would build, climax, and flow, in purposeful ways. First off, there’s the mastery with which he’s channeled his own breath through a reedless alto saxophone to create an open, conch-like efffect. And, in general, one can appreciate how the piece builds and winds from Sarin’s initial rhythms and Chapin’s airy incantations to a torrent of drums and full-throated saxophone line (with reed in place).

“Aeolus,” a gorgeous ballad-like composition spotlighting flute and bass, is one that carries great meaning for Chapin’s close friends and ardent fans. It’s the last tune he played in public, at a benefit in his hometown of Manchester, Connecticut on February 1, 1998. Two days later, Chapin was placed in intensive care; ten days past, he was gone. That poignant beauty was felt again, this time via video, during a late-March memorial at St. Peter’s Church in New York, where the final performance was screened. Here, the power of the music alone, as recorded years earlier, is revelatory. It speaks of the deep bond between Chapin, whose flute soars unfettered, and Pavone, whose plucked bass tethers Chapin’s every move.

On “Tweeter’s Little Adventures,” Chapin is back on sopranino horn. But if the voice sounds a bit more pinched and comical this time around, it’s an expressive imitation of the title’s main character, one of Chapin’s two cockatiels. Chapin had described it as “a portrait of Tweeter and his explorations of his environment (most the kitchen).” Of course, it was also an exploration of Chain’s musical environment—in this case, the kinds of unexpected angular song structures he favoured, and that owe a debt to another personal hero, Thelonious Monk.

For a man of such potent wit, the fact that Chapin flashes his circular-breathing abilities on a closer called “Changes Two Tires” was likely no accident. But the laughter (Chapin’s) that introduces this track is probably directed, playfully, at Pavone. The tune was inspired by a night when Pavone, after driving for hours and playing a trio set, went outside to fix a flat tire. When he finished, Chapin noticed another flat. “Not another one,” Pavone recalls saying, as they both realized that the bassist had changed the wrong one. “…changes two tires,” became the muttered punchline. As on “Night Bird Song,” Pavone’s figures here speak less of jazz basslines and more of Middle Eastern music. In any case, his vamps and lines underscore the well-timed slapstick exchanges of Chapin and Sarin.

Taken as just some time shared or as an important recorded document—and this CD is both—NIGHT BIRD SONG tells new and exciting stories. It distills a bit more of the spirit of a man who, when he passed, still had many secrets left to discover and perhaps reveal. It shares intimate details between close friends and collaborators. And, through a blend of newly heard compositions and familiar themes, it speaks of a moment when Thomas Chapin, having found his own voice, sensed his trio jelling: We get a whiff of the personal exuberance of a musician in his prime and with far-reaching ambitions having found himself smack in the perfect vehicle.

Review

Cadence Magazine

This 1992 recording of the Thomas Chapin Trio serves as a memorial to the leader who died in early 1998. It even includes a version of "Aeolus," the last tune he played in public. Still, this is no maudlin exercise; it is very much a celebration. And how could it be otherwise when the recording captures Chapin at his exuberant best. The laughter that introduces the closing track "Changes Two Tires" says as much about the tone of the session as the lovely, elegiac flute strains of "Aeolus."

Chapin loved to pen catchy, playful tunes with wide open improvisational possibilities, and then he made the most of those possibilities. "Alphaville" has all the energy of bop, with greater options for blowing. Chapin was a master of texture. I first encountered him on a session by guitarist Michael Musillami and I was struck by the richness of his flute tone. Well, his flute tone on this session was just as rich, and his alto saxophone was as rubbery as ever, and even his sopranino (an instrument with the potential to be the mosquito of the music world) is full-bodied. On "The Roaring S" he achieves a muffled brass sound by blowing into his mouthpiece without a reed using what looks like a trumpet player's embrochure. On "Sky Piece" he evokes one of his heroes by blowing two saxes at once. For all his adventurousness, he never loses the compositional thread.

Neither do bassist Pavone and drummer Sarin. Pavone – Chapin's frequent collaborator – provides a strong groundbeat, that for all its flexibility, never loses its dancing feet. Sarin stomps and sashays. Together they imply grooves, whether Latin, swing or even funk on "Little Tweeter," without losing their flexibility and getting locked into cliché. Both Pavone's and Sarin's solos emerge naturally from the texture as elaborations on their figures behind Chapin.

This is a welcome addition to Chapin's legacy.

© Cadence Magazine 2005. Published by CADNOR Ltd. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Cadence: www.cadencebuilding.com.